Could the President use the pretext of a terrorist attack to become a dictator in the United States?Of course, there are many approaches one could take to answering the question. I suppose the first step would be to reach agreement on the meaning of that term, "dictator." Pick your poison, most dictionaries will offer these definitions for the term:

"a person exercising absolute power, especially a ruler who has absolute, unrestricted control in a government without hereditary succession."

"a person invested with supreme authority during a crisis, the regular magistracy being subordinated to him until the crisis was met."

With those definitions of "dictator" in mind, we could restate the question just slightly this way:

Could the President use the pretext of a terrorist attack to assume supreme authority, that is, absolute, unrestricted control in the United States?Of a legal mind, and more particularly, a constitutional one, I take the question to mean:

- Do the Constitution and laws of the United States admit the possibility of a dictatorial President?

- Do the Constitution and laws of the United States provide solutions to a dictatorial President?

No, the Constitution and laws of the United States do not admit the possibility of a dictatorial President.

Yes, the Constitution and laws of the United States do provide solutions to a dictatorial President. Having laid those bare answers down, I will address some points of our history and our Constitution in the balance of this post.

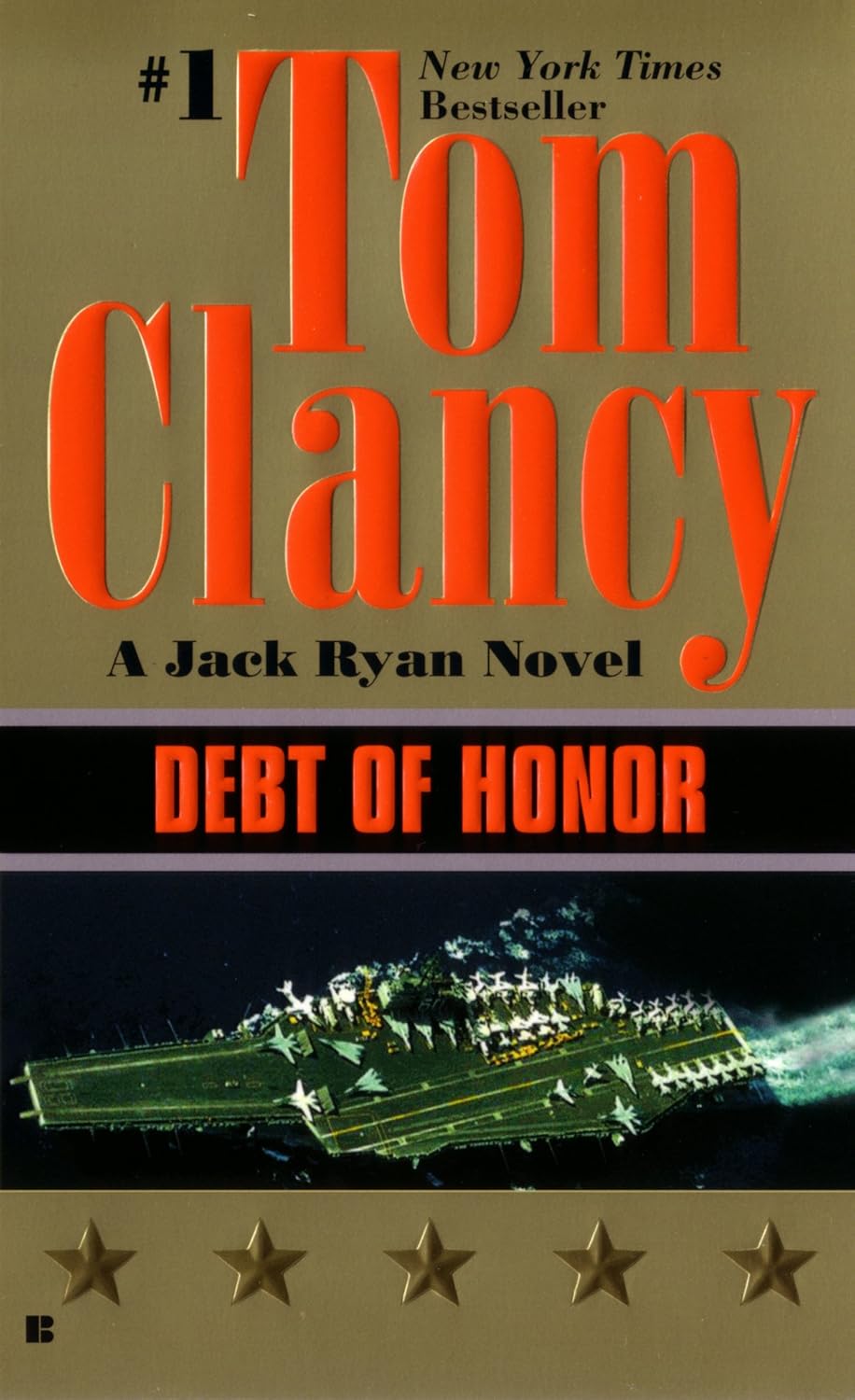

The late Tom Clancy produced a series of riveting novels that often brushed too close to real life. Clancy's 1994 novel, Debt of Honor, features an act of vengeance in which a Japanese national crashes a Boeing 747 commercial jet into the Capitol Building. In a decapitating twist, the crash occurs during an address to Congress by the President.

The late Tom Clancy produced a series of riveting novels that often brushed too close to real life. Clancy's 1994 novel, Debt of Honor, features an act of vengeance in which a Japanese national crashes a Boeing 747 commercial jet into the Capitol Building. In a decapitating twist, the crash occurs during an address to Congress by the President.The President, most members of Congress, and most of the President's cabinet are all killed. The attack occurs just moments the President obtained the assent of both Houses of Congress (as required by Section Two of the Twenty-Fifth Amendment) to his selection of perennial Clancy hero Jack Ryan as his Vice President. That put Ryan in the driver's seat of a badly damaged nation.

Of course, Debt of Honor was fiction.

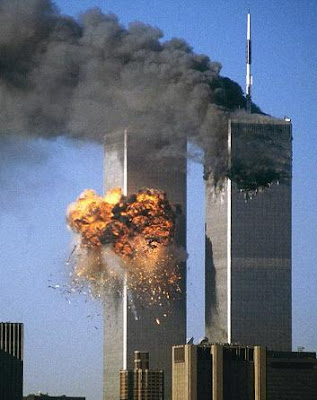

On September 11, 2001, however, that fiction came to life when terrorists hijacked commercial jet liners and crashed them into the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. [If you are inclined to think that the accepted explanation -- that terrorists organized and succeeded in this planned attack -- is simply cover-up to hide a homegrown plan that would justify American military interventions in Iraq and Afghanistan -- I hope you will continue to read. I am not taking on the issue of what caused 9/11. I am addressing what risk there is that, in the face of a future similar attack, we could find ourselves drawn under a domestic dictatorial regime.]

Now, the aftermath of Debt of Honor's fictional attack is told in Clancy's novel, Executive Orders. Interestingly, Clancy's President Ryan undertakes the role of Chief Executive and proceeds to govern principally through executive orders. President Ryan, in Clancy's scheme of things, validly governs by Executive Order because, in the absence of a Congress, necessary legislation to respond to threats and crises is unavailable. Unfortunately, Ryan's orders include at least one that is deeply troubling for a liberty minded People, namely a ban on interstate travel.

Seven years passed from publication of Debt of Honor to the destruction of the Twin Towers. The actual attack did not effect a decapitation of the federal government. President Bush, his Cabinet, the Congress, and the Courts were all secured against harm. As a nation, though, we reeled in stunned horror at the staggering devastation of the attacks. We were bereft of thought from the barrage of heart-rending images resulting from the terrifying and intimate attack.

Although imperfectly, the federal government -- President Bush and the Congress -- principally looked outward from the Nation and turned the energies of the government to the external homes and safe places of terrorists in order to secure the Nation from attack. [***Of course, the attack inflicted a substantial economic impact that needed correction, and the security implications of the 9/11 attack required evaluation, principally in the form of the 9/11 Commission.] There were domestic reactions, including the adoption of the PATRIOT Act, and the detention and interrogation of American Nationals within the United States.

In particular, the adoption of the PATRIOT Act constituted a dangerous assault on rights to personal liberty and property, by expanding categories and instances in which the surveillance apparatus of the federal government would be turned against Americans in their own homes and places of employment. The ACLU offered this brief, but pointed, explanation of the Fourth Amendment problems of the PATRIOT Act:

The Patriot Act increases the government's surveillance powers in four areas:From my legal practice -- consisting principally of defending the exercise of rights to freedom of speech, press, assembly and free exercise of religion -- I could see how, as a consequence of the attacks, courts became overly sympathetic to governmental claims that national security required what were, until then, unthinkable intrusions on the exercise of important liberties. The use of "Free Speech zones" to provide physical distance between protesters and government officials became a commonplace.

- Records searches. It expands the government's ability to look at records on an individual's activity being held by third parties. (Section 215)

- Secret searches. It expands the government's ability to search private property without notice to the owner. (Section 213)

- Intelligence searches. It expands a narrow exception to the Fourth Amendment that had been created for the collection of foreign intelligence information (Section 218).

- "Trap and trace" searches. It expands another Fourth Amendment exception for spying that collects "addressing" information about the origin and destination of communications, as opposed to the content (Section 214).

For example, each October, on the Sunday prior to the start of a new Term of Court, it is typical to see several Supreme Court Justices and other dignitaries attending the "Red Mass" held at St. Matthew's Cathedral in downtown Washington, DC. Catholic justices, including John Roberts, Antonin Scalia, and Anthony Kennedy often attend. When he was alive, Chief Justice Rehnquist attended, although not Catholic. Other non-Catholic justices that have, or do, attend, include Justice Stephen Breyer. The Red Mass is a tradition going back to Merry Olde England, in which prayers are offered for the guidance of the Holy Spirit as courts began their sessions.

A friend, and longtime client, Reverend Patrick Mahoney, wanted to express his views about court decisions prohibiting displays of the Ten Commandments on public property, so he went to the public sidewalk across from St. Matthew's to pray and express support for public displays of the Decalogue. Police threatened to arrest Mahoney. We litigated the closure of the sidewalks to demonstrators while they were being left open for use by other pedestrians, and while those attending the Red Mass were not stopped from their incidental exercise of First Amendment freedoms.

You could see the judge's eyes glaze over as the Government laid out its case for the supremely important interest in protecting the lives of these dignitaries. That interest, they argued quite successfully, required the suppression of constitutional liberties for the period of the Red Mass. The federal district court sustained the government's creation of a massive "speech free" zone next to the Cathedral, offering Mahoney and others the weak sop that the government would allow their activities in the "free speech zone" a block away.

Not one to simply surrender his rights, Reverend Mahoney and a stalwart band of like minded folk returned the next year for the Red Mass. As you can see in the accompanying photo, and read in the account by one of those who joined the event, federal police arrested everyone that stood and prayed on the sidewalk across the street from the Cathedral.

Not one to simply surrender his rights, Reverend Mahoney and a stalwart band of like minded folk returned the next year for the Red Mass. As you can see in the accompanying photo, and read in the account by one of those who joined the event, federal police arrested everyone that stood and prayed on the sidewalk across the street from the Cathedral.This incident is one example of the encroachments made on public demonstrations and protests after 9/11. I know of dozens of others.

Still, post 9/11, ours had not become a nation under the grip of a dictator. Americans remained free. If you doubt that assertion, consider the fact that we remained free to criticize and castigate verbally the President and the Nation's policies. Just take the example of Jon Stewart and his Daily Show. Send ups, like this one:

were common fare throughout nearly the entire two terms of the Presidency of George Bush. Yet, there were no nighttime disappearances of comics, or news readers, or critics.

This safe reality for Jon Stewart, David Letterman, and lesser comedic lights, readily contrasts with the fantastical dictatorship in the 2005 movie, "V for Vendetta." Here's the scene in which Stewart's cinema twin takes a comedic poke at that story's dictator, Chancellor Sutler:

And, of course, in the movie, as in real-life repressive regimes, the outcome for a defiant comic is at least painful. "Gordon Deitrich," the comic who roasted the Chancellor in "V for Vendetta" ultimately, off screen, pays the price for making light of the Chancellor.

And, of course, in the movie, as in real-life repressive regimes, the outcome for a defiant comic is at least painful. "Gordon Deitrich," the comic who roasted the Chancellor in "V for Vendetta" ultimately, off screen, pays the price for making light of the Chancellor.And, again, contrasting how unlike a dictator George Bush behaved during his tenure in office, word is just recently out that a well-liked TV personality in Communist China, Bi Fujian, will likely suffer harsh punishment for an indiscretion. He was videotaped singing a spoof version of a Communist Chinese anthem for dinner guests. Unfortunately for him, the video shows him referring to Mao Zedong as "that son of a b*tch" that made the nation miserable.

That's All Well and Good, But What Makes You Think that The President Could Not Assume Dictatorial Powers

Remember, the essence of dictatorship is absolute control.

Our frameworks of government, both at the State and federal level, proceed on the basis that government operates essentially in three capacities. First, governments make laws. Second, governments enforce laws. Third, government interpret the laws to insure that the enforcement of them is proper.

Our State governments are fractured into three divisions, governors, legislatures, and courts, just as the federal government is fractured by the Constitution into three nearly identical divisions, president, Congress, and judiciary. Of course, there is also a complete division of power of another kind between the States and the federal government. The States are the residual sovereign enterprises. Aside from certain express, precise powers granted by the States to the federal government, the States retain a large body of governmental power.

Bearing in mind that the fracturing of power is the normal state of affairs here, to succeed at the assumption of dictatorial power, the President would have an impressive "to do" list to complete:

You can see the difficulty that real dictatorship designs would present in the United States. The distrust of power in the Crown and Parliament that energized our fight for independence was given deep roots in our State forms of government, and those State government forms were the models on which the federal framework of the Constitution was based.

I do not dispute that circumstances could arise in which many Americans would look for strong leadership from Washington.

That, of course, is part of the terrible testament of the Great Depression and its severely burdensome legacy of federal government solutions and programs. Just looking back to the Great Depression, to the federal programmatic responses that Franklin Roosevelt and the Congress sought to impose, we can see how distant yet we were then from dictatorship.

The following excerpt describes the conflict between Roosevelt and Congress on the one hand and the Supreme Court on the other. Roosevelt and Congress enacted an alphabet of programs designed to pump money into the hands of those struggling to stay afloat after the Depression struck. The Supreme Court did not need an alphabet to grade the constitutionality of these programs, persistently giving an "F" to the recovery programs of the Administration:

The election-night jubilation was tempered, however, by an inescapable fear—that the U.S. Supreme Court might undo Roosevelt’s accomplishments. From the outset of his presidency, FDR had known that four of the justices [] would vote to invalidate almost all of the New Deal. They were referred to in the press as “the Four Horsemen,” after the allegorical figures of the Apocalypse associated with death and destruction. In the spring of 1935, a fifth justice [] began casting his swing vote with them to create a conservative majority.

During the next year, these five judges, occasionally in concert with others, especially Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes, struck down more significant acts of Congress—including the two foundation stones, the NRA and the AAA, of Roosevelt’s program—than at any other time in the nation’s history, before or since. In May 1935, the court destroyed FDR’s plan for industrial recovery when, in a unanimous decision involving a kosher poultry business in Brooklyn, it shot down the blue eagle. Little more than seven months later, in a 6 to 3 ruling, it annihilated his farm program by determining that the Agricultural Adjustment Act was unconstitutional. Most of the federal government’s authority over the economy derived from a clause in the Constitution empowering Congress to regulate interstate commerce, but the court construed the clause so narrowly that in another case that next spring, it ruled that not even so vast an industry as coal mining fell within the commerce power.Roosevelt, buoyed with a landslide 1936 election victory, devised the "Court packing" plan. "Court packing" would require Congress to enlarge the total number of Justices on the Court each time a sitting justice reach 70 years of age. In his radio address defending the plan, Roosevelt put the entire plan down as a method of improving judicial efficiencies, and denied he was seeking results by appointing reliable votes to the Court to change the Court's prevailing philosophy toward federal governmental programs for the recovery.

The Senate did not proceed with consideration of the proposed legislation. The need for the plan abated, however, when in the soon aftermath of Roosevelt's proposal, in a series of decisions, the Court sustained New Deal programs and minimum wage laws.

The important take away from the episode, for our purpose, is that, even at the apogee of his popularity, when Roosevelt might correctly have concluded that he could act unilaterally, he chose not to do so. Yes, he made effective use of the "bully pulpit" of his office. He did not seize dictatorial control.

Nor did John Kennedy, when he might have under the veil of the Cuban Missile Crisis. Nor did Andrew Johnson, Chester A. Arthur, Theodore Roosevelt, nor Lyndon Johnson, although each succeeded to the presidency as the consequence of an assassination of the President under whom they served. Nor did James Madison when the British attempted to reconquer her former colony, including burning the District of Columbia, during the War of 1812.

Still, we have not yet had such a complete breakdown of order in the Nation that space has been made for, and a dictator did in fact arise. We have had close calls. The Civil War brought us close to the brink.

During the Civil War, Abraham Lincoln suspended writs of habeas corpus. While the capture of spies might be expected to elicit military detention, reporters and public persons were subject to detention, even a St. Louis minister was seized and held without access to the writ of habeas corpus. The Great Writ is part of our heritage from the English common law.

When granted by a court, the writ of habeas corpus compels executive officers to come before the issuing court, bringing with them the prisoner or detainee that sought the writ, so that the court can examine the reasons for the arrest and detention of the prisoner. Suspending the Great Writ certainly has the feel of dictatorial excess, but is typical under martial law. Lincoln's excesses, however, extended to tolerating arrests, unlimited detentions, and executions of deserters. Perhaps Lincoln's most crass act of was his order for the mass hanging of 38 Sioux Indians, to take place two days after Christmas, 1862.

During war, Presidents are, it seems, most tempted to impatience with the political process, and most likely to assume that the Constitution has rested in their hands, rather than with Congress, the determination of national policy.

Harry Truman, after attempting to use regulatory methods to restrain inflation, faced the possible suspension of steel manufacturing during the Korean Conflict. To avoid that outcome, Truman ordered privately owned steel manufacturing facilities seized by the government, to be operated by the government in place of the owners of the companies. Truman's decision was roundly rejected:

The public reaction was swift and savage. The great majority of newspapers rejected this sweeping doctrine of executive power. An editorial in the New York Times rebuked Truman for creating "a new regime of government by executive decree," a system of government that was inconsistent "with our own democratic principle of government by laws and not by men."[] The Washington Post predicted that Truman's action "will probably go down in history as one of the most high-handed acts committed by an American President."[] Other newspapers weighed in with various forms of denunciation, excoriating Truman for trying to exercise "dictatorial powers."[] The Atlanta Constitution called Truman's order "dangerous"; the Boston Herald objected to Truman's effort to "dictatorially" bypass Congress by making his own law; the Christian Science Monitor accused him of precipitating "a constitutional and political crisis"; and the Detroit Free Press warned that unless someone stopped Truman's exertion of power "our whole constitutional system is doomed to destruction."[]Truman's decision resulted in litigation that came to the Supreme Court. In Youngstown Sheet and Tube Co. v. Sawyer, the Supreme Court rebuked Truman's overreach and rejected the power of the President to engage in the unilateral seizure of private industry.

Even short of war, when sufficient unrest has existed in regions of the country, Congress has granted limited authority in special circumstances to the President to impose martial law. In the aftermath of the Civil War and after ratification of the Reconstruction Era Constitutional Amendments, Congress passed a series of statutes, each of which was called "The Enforcement Act." One of those acts, adopted April 1871, addressed the rank lawlessness into which several South Carolina counties had descended. The key provision of the Enforcement Act, authorizing the President to take all necessary steps to restore order, stated:

That in all cases where insurrection, domestic violence, unlawful combinations, or conspiracies in any State shall so obstruct or hinder the execution of the laws thereof, and of the United States, as to deprive any portion or class of the people of such State of any of the rights, privileges, or immunities, or protection, named in the Constitution and secured by this act, and the constituted authorities of such State shall either be unable to protect, or shall, from any cause, fail in or refuse protection of the people in such rights, such facts shall be deemed a denial by such State of the equal protection of the laws to which they are entitled under the Constitution of the United States; and in all such cases, or whenever any such insurrection, violence, unlawful combination, or conspiracy shall oppose or obstruct the laws of the United States or the due execution thereof, or impede or obstruct the due course of justice under the same, it shall be lawful for the President, and it shall be his duty to take such measures, by the employment of the militia or the land and naval forces of the United States, or of either, or by other means, as he may deem necessary for the suppression of such insurrection, domestic violence, or combinations; and any person who shall be arrested under the provisions of this and the preceding section shall be delivered to the marshal of the proper district, to be dealt with according to law.During the administration of President Grant, in fact, ten counties in South Carolina devolved into such a condition of insurrection and violence that Grant declared martial law and deployed military forces to restore order.

Now, there are other occasions, in answer to riots and civil disturbances in which governors call out their State's National Guard and reserve units. Recent unrest in Baltimore, Maryland, and in Ferguson, Missouri, has led to deployment of such State assets. Still, that does not amount to dictatorial power in the President, or in the Governors that make such use of assets.

What Remedy Would Answer Such a Seizure of Power by a President?

An immediate remedy to every presidential excess, to every presidential abuse of power, lies in the Congress, the directly elected representatives of the People. I speak of the three pillars of constitutional authority of the Congress: budget, oversight, and impeachment.

The Congress alone has the power to lay taxes and to make expenditures. In respect of taxing and spending, the President serves the policies and plans of Congress. The beauty of our system is that in the absence of express authority, no money may be expended by the government. In every case, the willingness of Congress to stand firm on its design for taxing and spending will result, must result, in capitulation by the President. If he does not give place to the designs of Congress no new expenditures would be authorized, and the government would go out of operation.

It is a position of inferiority and weakness from which the President proceeds. The Framers designed these two powers, to tax and to spend, in just this way with the view that the body most responsive to the desires of the People should be the place where such powers were reposed. So, to the extent that a dictatorial-like President would seek to give effect to his designs by taxation and spending, Congress has immediate and effective power to obstruct.

Congressional oversight power is also considerable. To call to account the officers and agents of the government, to require that particularized detail of function be provided, and provided under oath, on pain of contempt of Congress, these are important tools of the Congress.

We do know, with respect to oversight, that to some extent, the value of this tool is lessened by the necessary give and take that we usually witness between Congress and the Executive. Disputes over whether Cabinet officers will appear to testify on a matter, whether their testimony will be given under oath (ostensibly giving rise to a risk of criminal prosecution for lying in cases in which a witness does so) are common place in each instance in which the two branches are in the hands of opposing political parties.

Finally, in the ultimate moment of dispute between the branches, Congress possesses the power to impeach the President, officers of the United States government (including members of the cabinet and others), and judicial officers. That power is absolute. There is no aspect of it that is subject to consideration and approval by the President. There is no aspect of it that is subject to review by the Supreme Court.

Let us suppose, though, that the President, in dictatorial fashion, disbanded the Congress. Clancy's Ryan did not disband Congress, it had been virtually extinguished by a terrorist attack. Hitler's Nazi Party did not disband the Reichstag, the Reichstag itself granted autocratic power to the German Chancellor. King George III did, in fact, disband colonial legislative bodies. The Declaration of Independence lists that act among several justifying the severance of our ties with the English Crown and Parliament.

So, suppose that a dictatorial President co-opts the Congress, as Hitler did the Reichstag, or disbanded the Congress as did King George III. What further measures would remain to protect the People from the depredations of a dictator?

The resistance of the Depression era Court to the New Deal programs of Roosevelt show that the Court possesses the necessary goods to deny legitimacy to the conduct of the President in such cases. Moreover, the Civil War era Supreme Court denied legitimacy to the use by Lincoln's military of military tribunals for the trial of civilians so long as the civil courts of the State were available for the purpose. Even going back to the administration of Thomas Jefferson, the Supreme Court, in Marbury v. Madison, chastised the President for withholding certain judicial commissions issued by President Adams but not delivered to the appointed officers prior to the expiration of Adams' term.

In each of these cases, the Court demonstrated a will to preserve its sphere of authority against Executive invasion. Of course, the President could as easily then disband a Court hostile to his actions.

Still, multiple layers of resistance to tyranny remain.

The States are not the President's to own, to direct, and to control. Each of them would be in a position to resist such action. Democratic Governor Orval Faubus used the Arkansas National Guard to resist federal court ordered integration of the Little Rock schools. That action worked but only until the Arkansas National Guard complied with an order from President Dwight Eisenhower, federalizing the Guard, and ordering them to supervise the peaceful integration as ordered by the federal court.

Still, the States remain a substantial dispersed bastion for resistance to dictatorship. The entire enterprise of the federal government tends to depend on cooperation. How the venture could be carried forward in the case of a malign dictator is too unlikely to imagine.

Finally, there is that one further layer of security against tyranny. The Daily Caller reported on firearms ownership statistics in the United States in a post in November 2014. That post suggested that Americans owned, then, approximately 240,000,000 guns, rifles, pistols, and shotguns, including 47,000,000 guns purchased after 2008. Our nation was born in blood, aided in its labor and delivery by the militia: armed men who brought their own firearms to the cause, and who were convinced of the right of their cause against a tyrannical regime that struck at their legislatures, their courts, and their rights as free men.

One simply hopes that we never need to rely on the private American arsenal for such a reason as internal tyranny.