|

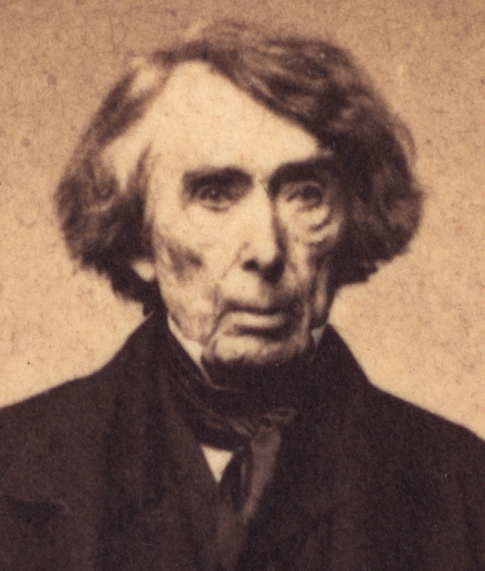

| Roger Taney |

Yet, there you have Jefferson, penning among the most powerful and persuasive declarations of the natural rights of men, acknowledging that Nature, and Nature's God, endowed us each with the unalienable rights to life, to liberty and to pursuit of happiness. All the while, Jefferson's agriculture enterprises, such as they were, rested on the backs of African slaves. Not free black tradesmen, craftsmen and laborers, but slaves.

That the wrong of slavery among our Founders was known, and understood, cannot be rightly disputed.

Still, the compromises that are essential to politics, it seems, compelled the Framers to conclude that for the enterprise of independence to succeed the view of the moral wrong of slavery must give place to the expedient need of unity among the manufacturing colonies and the agricultural colonies. So our Declaration of Independence did not declare the liberty and equal status of those held to involuntary servitude or slavery.

When the States formulated a general government for the Nation, slight regard was given to the ongoing stain that slavery placed on hearts that professed such love of liberty. So the Constitution did not end slavery, and it ensconced the idea of slavery in it by including the counting of slaves (each slave reduced in count value to 3/5ths of a person) in the enterprise of apportioning representatives in the Congress. The States did include a provision that offered a possibility that Congress could eventually end the international importation of slavery, although it would not restrict internal trading of slaves:

The Migration or Importation of such Persons as any of the States now existing shall think proper to admit, shall not be prohibited by the Congress prior to the Year one thousand eight hundred and eight, but a Tax or duty may be imposed on such Importation, not exceeding ten dollars for each Person.As it happened, Congress did act to prohibit the importation of slaves, in 1807, 1818, 1819, and 1820.

Nonetheless, a population of about 1.5 million slaves lived in the US at the time of the 1820 decennial census (out of a total population approaching 10 million). By the time of the enactment of the Thirteenth Amendment, prohibiting slavery and involuntary servitude, the slave population in the US grew to about 4 million.

Although the Constitution expressly contemplated a ban on importation of slaves, it was silent as to the long-term solution to the Peculiar Institution. Because of regional differences, it became a source of ongoing political discord. Congress undertook several efforts at legislative solutions to the Peculiar Institution. Although the supply of imported slaves would be virtually eliminated, the Nation had to consider how to address the possible expansion of slavery with the Nation. And the slave population did, in fact, grow, quadrupling in a forty year period.

Congress took legislative action in 1820, with the Missouri Compromise, in 1850 with the Compromise of 1850, and in 1854 with the Kansas-Nebraska Act.

The Missouri Compromise:

- brought Maine into the Union as a free state and Missouri as a slave state

- prohibited slavery in the federally controlled territories

- prohibited slavery in any new States above the 36º 30´ latitude line except Missouri

- maintained the balance of free state and slave state Senators in the US Senate.

- brought California entering the Union as a free state

- granted the New Mexico and Utah Territories the right to decide the slavery question for themselves

- abolished slave trading in Washington, DC

- bolstered the Fugitive Slave Law by requiring free States to assist in the return of escaped slaves to their masters.

- granted to the residents of Kansas and Nebraska the right to decide the slavery question for themselves

- removed the slavery prohibition above the 36° 30´ latitude previously set by the Missouri Compromise.

These compromises reflected the work of the representatives of the People, in the Congress, seeking to resolve the continuing divide and conflict among the States on the question of slavery. Imperfect as they may have been, the compromises determined conditions for the admission of new States, regulated the territories under the supervision of the general government because they had not yet been organized into States, and provided balance in the admission of States between Free nor Slave States.

And it is at this point that we discover how the head of Roger Taney ends up in the Bag of Shame.

Taney, Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, wrote the 1857 decision of the Court in Dred Scott v. Sandford. Dred Scott had sued his owner in federal court, seeking a judgment on three personal injury claims arising from assaults on Scott, his wife, and their child. Because the Constitution limits the kinds of cases claimants can bring to federal courts, Dred Scott relied on "diversity of citizenship" because he and Sandford resided in different States.

A brief detour here will illuminate why Taney's head is in the bag.

Federal courts do not have the power or right to decide case except where that power is expressly granted to them in the Constitution, or in statutes enacted by Congress using the power given to it in the Constitution to create federal courts and craft the rules for their jurisdiction. So, when a federal court is drawn into a controversy between antagonists, it has a constitutional duty to insure that its powers are properly exercised or restrained. That duty is honored by a court proceeding first to answer the question whether the Constitution or federal statutes authorize it to hear the particular case before it. In cases where a court concludes that the Constitution and laws do not authorize the suit, its duty is done by dismissing (throwing out) the lawsuit.

When a court dismisses a lawsuit because it lacks the power (jurisdiction) to hear the case, that does not reflect on the moral character of the underlying claims, or on whether sufficient evidence exists to prove the claims, or any other substantive question. It simply reflects the duty of federal courts to confine themselves to the boundaries of the constitutional duties.

Bearing that duty in mind, we can quickly see how Taney's head ends up in the Satchel of Embarrassments.

Dred Scott claimed that, because he became a free man by his extended presence in a free State and in a free Territory at the deliberate cause of his previous owner, he, Scott, acquired the status of a free black. As a free black, Scott contended he had the right, as a citizen, to bring the lawsuit seeking the judgment on assaults committed on him, his wife and his child by his owner.

Taney concluded, however, that even if he were a free black, he could not be a citizen. In fact, Taney construed the Constitution to exclude any possibility that free blacks could ever be citizens:

But Taney did not stop with his conclusion that the Court lacked jurisdiction to hear Scott's claim. He then proceeded to conclude that Congress, in its enactment of the Missouri Compromise of 1820, had violated the Constitution. In his view, and the Court's, the Constitution did not give Congress power to regulate slavery in the territories not yet organized as States. Proceeding from that conclusion, prohibitions on slavery in the territories that lay above the 36º 30´ latitude line were invalid.

Taney's conclusion, that even free born blacks were not, could never be, citizens of the United States or of the States, helped to precipitate the Civil War. His conclusion that Congress could not regulate slavery in the territories risked delegitimizing Congressional regulation of the slave trade in the territories. It took a Civil War and two amendments to the Constitution to eradicate Taney's stain on the Constitution.

And it is at this point that we discover how the head of Roger Taney ends up in the Bag of Shame.

Taney, Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, wrote the 1857 decision of the Court in Dred Scott v. Sandford. Dred Scott had sued his owner in federal court, seeking a judgment on three personal injury claims arising from assaults on Scott, his wife, and their child. Because the Constitution limits the kinds of cases claimants can bring to federal courts, Dred Scott relied on "diversity of citizenship" because he and Sandford resided in different States.

A brief detour here will illuminate why Taney's head is in the bag.

Federal courts do not have the power or right to decide case except where that power is expressly granted to them in the Constitution, or in statutes enacted by Congress using the power given to it in the Constitution to create federal courts and craft the rules for their jurisdiction. So, when a federal court is drawn into a controversy between antagonists, it has a constitutional duty to insure that its powers are properly exercised or restrained. That duty is honored by a court proceeding first to answer the question whether the Constitution or federal statutes authorize it to hear the particular case before it. In cases where a court concludes that the Constitution and laws do not authorize the suit, its duty is done by dismissing (throwing out) the lawsuit.

When a court dismisses a lawsuit because it lacks the power (jurisdiction) to hear the case, that does not reflect on the moral character of the underlying claims, or on whether sufficient evidence exists to prove the claims, or any other substantive question. It simply reflects the duty of federal courts to confine themselves to the boundaries of the constitutional duties.

Bearing that duty in mind, we can quickly see how Taney's head ends up in the Satchel of Embarrassments.

Dred Scott claimed that, because he became a free man by his extended presence in a free State and in a free Territory at the deliberate cause of his previous owner, he, Scott, acquired the status of a free black. As a free black, Scott contended he had the right, as a citizen, to bring the lawsuit seeking the judgment on assaults committed on him, his wife and his child by his owner.

Taney concluded, however, that even if he were a free black, he could not be a citizen. In fact, Taney construed the Constitution to exclude any possibility that free blacks could ever be citizens:

The question before us is whether [free blacks] compose a portion of this people, and are constituent members of this sovereignty? We think they are not, and that they are not included, and were not intended to be included, under the word "citizens" in the Constitution, and can therefore claim none of the rights and privileges which that instrument provides for and secures to citizens of the United States. On the contrary, they were at that time considered as a subordinate and inferior class of beings who had been subjugated by the dominant race, and, whether emancipated or not, yet remained subject to their authority, and had no rights or privileges but such as those who held the power and the Government might choose to grant them.Now, at the point in time where Taney concluded that, even were it true that Scott had acquired the status of a free black, he could not be a citizen, and therefore was not entitled to have access to the federal courts based on "diversity of citizenship" between himself and his current owner, the case properly should have ended. There would be no reason to engage in any further reasoning or discourse on issues that were affected by the dispute, once the Court reasoned that it lacked jurisdiction.

But Taney did not stop with his conclusion that the Court lacked jurisdiction to hear Scott's claim. He then proceeded to conclude that Congress, in its enactment of the Missouri Compromise of 1820, had violated the Constitution. In his view, and the Court's, the Constitution did not give Congress power to regulate slavery in the territories not yet organized as States. Proceeding from that conclusion, prohibitions on slavery in the territories that lay above the 36º 30´ latitude line were invalid.

Taney's conclusion, that even free born blacks were not, could never be, citizens of the United States or of the States, helped to precipitate the Civil War. His conclusion that Congress could not regulate slavery in the territories risked delegitimizing Congressional regulation of the slave trade in the territories. It took a Civil War and two amendments to the Constitution to eradicate Taney's stain on the Constitution.